Bioleaching, also known as bio-mining, employs microbes to oxidise metals as part of their metabolism. The process has been widely used in the mining industry, where micro-organisms are used to extract valuable metals from ores. More recently, this technique has been used to clean up and recover materials from electronic waste, particularly the printed circuit boards of computers, solar panels, contaminated water and even uranium dumps.

Professor Sebastien Farnaud, along with colleagues in the university’s Bioleaching Research Group, have identified that bacteria, including Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans and other non-toxic species, can target and recover the individual metals in EV batteries, reducing the need for non-eco-friendly techniques which involve high temperatures or toxic chemicals.

These purified metals constitute chemical elements, and so can be recycled indefinitely back into multiple supply chains.

“Most of the world’s lithium lies under the Atacama Desert in South America, where mining threatens local people and ecosystems” said Sebastien Farnaud, Professor of Bio-innovation and Enterprise. “Instead of mining new sources of these metals, why not reuse what’s already out there? Lithium-ion batteries are currently recycled at a meagre rate of less than 5 percent in the EU and most batteries that do get recycled are melted and their metals extracted. These plants are expensive to build and operate, and require sophisticated equipment to treat the harmful emissions generated by the smelting process. Despite the high costs, these plants rarely recover all valuable battery materials. Bioleaching, on the other hand, can offer a more sustainable and effective solution to recycling electric car batteries.”

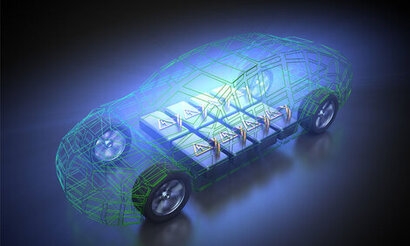

These findings come at a critical time, as the pressure to manufacture EVs in line with the UK government’s plans to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030 is expected to cause a surge in demand for metals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese.

For additional information: