"The ugly truth is that 58 percent of the energy generated in the United States is wasted as heat," said Yue Wu, a Purdue University assistant professor of chemical engineering. "If we could get just 10 percent back that would allow us to reduce energy consumption and power plant emissions considerably."

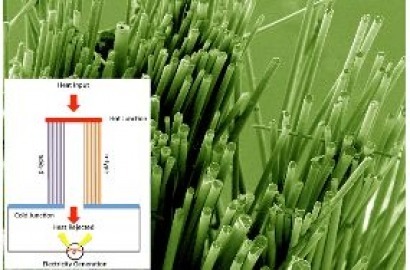

Researchers have coated glass fibers with a new "thermoelectric" material they developed. When thermoelectric materials are heated on one side electrons flow to the cooler side, generating an electrical current.

Coated fibers also could be used to create a solid-state cooling technology that does not require compressors and chemical refrigerants. The fibers might be woven into a fabric to make cooling garments.

The glass fibers are dipped in a solution containing nanocrystals of lead telluride and then exposed to heat in a process called annealing to fuse the crystals together.

Such fibers could be wrapped around industrial pipes in factories and power plants, as well as on car engines and automotive exhaust systems, to recapture much of the wasted energy. The "energy harvesting" technology might dramatically reduce how much heat is lost, Wu said.

Findings were detailed in a research paper appearing last month in the journal Nano Letters. The paper was written by Daxin Liang, a former Purdue exchange student from Jilin University in China; Purdue graduate students Scott Finefrock and Haoran Yang; and Wu.

Today's high-performance thermoelectric materials are brittle, and the devices are formed from large discs or blocks.

"This sort of manufacturing method requires using a lot of material," Wu said.

The new flexible devices would conform to the irregular shapes of engines and exhaust pipes while using a small fraction of the material required for conventional thermoelectric devices.

"This approach yields the same level of performance as conventional thermoelectric materials but it requires the use of much less material, which leads to lower cost and is practical for mass production," Wu said.

The new approach promises a method that can be scaled up to industrial processes, making mass production feasible.

"We've demonstrated a material composed mostly of glass with only a 300-nanometer-thick coating of lead telluride," Finefrock said. "So while today's thermoelectric devices require large amounts of the expensive element tellurium, our material contains only 5 percent tellurium. We envision mass production manufacturing for coating the fibers quickly in a reel-to-reel process."

For additional information: