The daughter of an engineer who spent a quarter century working on the Hubble space telescope, Miebach’s art focuses on the intersection of creativity and science and the visual articulation of scientific observations.

But while that description might lead one to believe she spends her days in front of an Apple computer spinning out “art” with the aid of a graphics program, that assumption couldn’t be more wrong.

In fact, Miebach’s chosen medium is basket-weaving, and with it over the course of the past decade, she has interpreted scientific data related to astronomy, ecology and meteorology in three-dimensional space.

As Miebach describes below, the idea came to her while attending the Harvard University Extension School in Cambridge, Mass. , in the US. At the time she was primarily studying astronomy and physics, but she felt something was absent in the two-dimensional materials with which the courses are traditionally taught.

In the decade or so that has elapsed since, she’s charmed and inspired an ever-growing and appreciative audience with tactile representations of environmental change. One way she has done that is to expand her work to include music that grows directly out of the data she collects.

Of this evolution in her work, Miebach told Renewable Energy Magazine that she feels “a bit uncomfortable” grafting the description of “composer” onto her CV both because of her lack of formal education in music and because, “the musical compositions I create aren’t really compositions, but more transposing of data onto a visual matrix that reads like a musical score.”

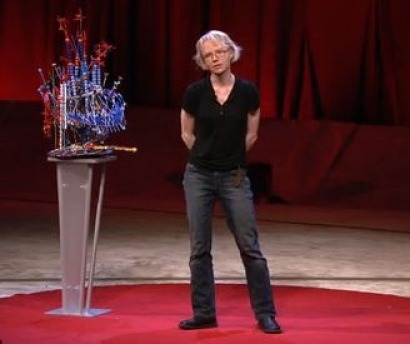

During a recent TED lecture in the US, Miebach described her work, at its most basic level, as a 3D graph of weather data in which every bead and color and band represents a weather element that can also be read as a musical note.

“Weather is an amalgam of systems of that largely invisible to us,” she said. Her art serves the purpose of making it seen, heard touched.

“Every concrete form reveals a relationship and inter-relationship that might not come across in a graph,” Miebach continued, adding, “I see my work as an alternative entry point into the complexity of science.”

During a recent conversation she extended that interpretation to include the complexities of climate change – the pre-eminent driver behind the push for the adoption of renewable energy and energy efficiency measures across the globe.

How did you get involved in bringing science and art together?

That actually began 11or 12 years ago, and it really started not with weather, but with astronomy. I was taking night classes at Harvard University, through its extension school program. I took classes in the physics and the astronomy department and at the same time, very serendipitously, I was also taking a class in basket weaving.

It was a kind of weird situation where I would go to the lecture hall at Harvard with my bucket and my sprayer and all the tools and materials you need for basket weaving. Astronomy was absolutely fascinating. It just blew my mind as I was studying it, and I think what drew me to the subject in the first place was my father had worked for over 25 years as an engineer for the Hubble space telescope project. As a result, we always had images of space around the house, but I never actually learned about astronomy until later.

What struck me about it was, here I was studying the deepest of space and the deepest of time and yet all you ever had in astronomy were these images that were projected, either on a computer screen or on a projector wall, and that to get a real sense of physical space in astronomy is very difficult. You can’t go out and touch a star or jump in a spaceship and tour the solar system.

As somebody who learns kinesthetically, through really manipulating things and touching things, I felt like I had to somehow penetrate that two dimensional projection in order to get a real sense of what this was all about and to understand that astronomical space.

And so for my final paper, rather than writing a paper, a ended up creating a sculpture with my basket-weaving. The very first sculpture I made was based on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, which is a very beautiful and well known graph in astronomy that plots the evolution of stars based on just two variables.

[Note: The Hertzsprung–Russell diagram is often described as a “scatter graph” of stars showing the relationship between the stars’ absolute magnitudes or luminosities versus their spectral types (colors) and effective temperatures.]

So I used that graph and converted it into a three-dimensional model through basket-weaving, and it was one of those instances where you kind of feel that little light bulb go off, because it made me realize that turning questions I had about science into 3D objects was actually a way of understanding them better. As idiosyncratic as that might sound [laughs], it seemed very logical to me.

Had you by this point already conceived of the basket as a grid?

Well, basically, I went from creating very didactic three-dimensional models of graphs to that idea. What if the basket is not just a vehicle to create a model, but actually serves as a simple grid? Because when you look at a basket, it has horizontal elements and vertical elements and they also happen to exist in 3D.

So very much as with painting by numbers, I began to think of the basket as a grid to plot numbers on – sculpture by number. From there the very first thing I looked at were solar and lunar calendars and trying to understand how these solar and lunar cycles effect eco-systems here on Earth. That led to a series of sculptures that looked at daylight and nighttime hours here on Earth. I did one on the Arctic, another on the Antarctic, for regions a little bit closer to the equator, and I realized, using the basket as a grid, I started to see a lot of warping going on.

What was happening was that the numbers I was converting was starting to create really strange forms. I use traditional basket-weaving material called reed because it has a lot of natural tension in it, and what that ensures is that the numbers dictate the form and not me. If I were to use something like metal or wire, I would be completely dictating the form, rather than the numbers dictating the form.

From this series of sculptures I went on to a subsequent series of sculptures that looked at tidal rhythms in different areas of the Earth.

When did you start examining weather patterns?

About six years ago, I found myself on Cape Cod for two consecutive artist residencies that I had there – so it was 14 months of living on the Cape, which is surrounded by ocean and its an incredible landscape, and it seemed like a really dumb idea to shut myself up in a studio. I needed an excuse to get out there.

At the same time, there were two science educators from Tufts University who were field testing a project for grade K-12 students on climate change. The premise of this project was based on this small PVC cube which you would stick into any kind of environment – your backyard, an ocean, a forest, what have you – and you would think of this cube as a mini-environment and you would try to extract as much information as you could from that: the temperature, the barometric pressure, wind and so forth. Then based on what you found going on in the cube, you would try to extrapolate what’s going on in the larger environment around it.

They knew about my work in data translation into 3D forms and asked me to field test their project on Cape Cod. This gave me the chance to collect my own weather data. Prior to this time, the data I incorporated into my sculptures had always come from research institutions, weather stations or universities… it was always numbers somebody else had collected.

This was a much different experience. It takes an incredible amount of discipline and rigor to get really good data, so there was a huge learning curve going on my end in regard to weather and data collection and the discipline it takes and so forth.

So for 14 months, I went out to this beach on Cape Cod and using very simple data collection devices, I would collect weather data every day rain or shine, and then I would go back to my studio and compare my findings to local weather stations, historical data, larger studies on climate change and weather patterns. At that point, I would start to translate all of that data into sculptures.

That’s how I got into weather, and even though the relationship with the scientists soon kind of meandered out, I stuck with weather because its an endless pool of information that always changes. It seems like I can go on forever.

How did the music come into this?

The music came into the translation process after I moved into the city. After living on Cape Cod for two years, the next places I lived were all urban environments, and it is a lot more difficult to record weather in an urban environment that it is on Cape Cod. On the Cape, there are no obstructions, the weather is all around you, the ocean is right there – the weather is right there in your face.

When you try to record weather in an urban environment, you have a lot more factors to deal with: You have the infrastructure of the city, you have building materials that either absorb heat or reflect heat, you have the lack of vegetation, you have these heat bubbles that literally trap heat over cities. So you can go down one street and record certain conditions and then walk down another and you get a totally different reading. The question then becomes, what are you actually recording? Are you recording the city? Or are you recording the weather? What are these numbers actually about?

As a result, there was a lot more dissonance in the numbers I was recording. Weather isn’t just a matter of looking at numbers; weather is an interaction between natural systems and the existing environment. To understand weather, you also have to understand the environment in which you are measuring or observing it.

Rather than write this off simply as bad data, I wanted to find a way to give these nuances a voice. The problem with a basket is it’s a grid and you can push and prod it only so far before gravity will just pull it apart.

As a result, I wanted to find some kind of mediator that would allow me to retain the integrity of the information I was gathering. I wanted to find a way to bring in nuance without alternating the information. Musical notation became a way of doing that.

The problem is that I don’t play music, nor do I read music. When I write these scores, I say I am not a composer, I am a translator. So what I do is I try to devise some sort of visual matrix that will allow me to translate the information into a score that musicians can work with, but also a score that I can work with as a sculpture. Now the information goes from my instruments and observations to a musical matrix to a sculpture. The result is the sculptures look very different that they did before because they now integrate the visual language of the musical score.

How have you dealt with the issue of climate change in your art?

Well, when I began, I looked at everything through the filter of climate change. It goes back to working with those scientists on Cape Cod, and everything kind of came though that filter. One thing I learned – and very quickly – is I can’t really understand the complexity o climate change until I understand the complexity of weather. So for me it was a matter of kind of zooming back to the local and stepping away from the global perspective.

It was a case of really trying to understand the meteorological interactions in my own environment. So now what I am trying to do is trying to reveal the complexity of weather. They are not overt statements on climate change. Because I think it is when we see how incredibly interconnected weather systems are, that’s really when you begin to understand the interconnection of climate change.

That was my take away from watching your TED presentation online. It seemed like your art and that very vivid music was a way to connect with a weather phenomenon in a very different way…

I think what’s really interesting in working with the musicians who are interpreting these scores is it brings in alternative ways of accessing these complex systems of science that are usually presented to us via graphs or in papers on climate change. It is an entry point into the complexity of science.

The thing that surprises me about my work is how many questions it triggers in people, and also how people always tell me weather stories. They may not understand what the piece is about, but everybody has a story about weather and it’s always a storm that they lived through or a blizzard or something. What I find very interesting is how important your own visceral memory of weather is and how that comes into the way you record information.

I’m being a little bit vague here, but I guess I’m beginning to be really interested in how incredible sensitive the human body is as a weather station. We pick up a lot more information about weather than we are aware of, and a lot of it happens peripherally. One thing I learned on Cape Cod going out every day taking these recordings is you go into these environments and while your focus is collecting weather data, you start noticing other things: the bird behavior, the clouds, what the day smells like, how sound changes with changes in weather patterns. These are things you typically register subconsciously, but its part of the way you understand weather. This is where instruments are weak, because they miss that nuance.

What kinds of feedback do you get when you show these pieces?

One of things I hear, from science teachers, is a strong response to the tactile nature of these works. A lot of them talk about the classroom experience as being very much like what I experienced while studying astronomy. Today, a lot of science education happens on a computer, so this tactile experience of understanding information is actually pretty rare. This brings it back to assigning an abstract number a representative physical object. So there’s interest in that from educators.

The music also seems to trigger a lot of response. I don’t completely understand why it does, but it does. It was when I started to combine the data, the sculpture and the music that it really started to trigger a larger discussion, particularly in the new media field, in the technology field and in the science field.

Early you talked about the changes moving from Cape Cod to an urban environment brought to your work. And of course, along with the discussion of issues like climate change, there’s also a complimentary discussion going on about better, more efficient urban design, green building and energy efficiency. Does the evolution in your work inspire much conversation about these things?

Hmm… that’s a good question.

Does the evolution of your work make you think about these things differently?

Well, the way I think about it goes back to when I was recording weather data in the city and realizing how easy it was to forget weather in the city, to a sense. A city is a very dynamic set of systems that sort of engulf you and on an average day you can pretty much forget about weather. You notice it. But it is nowhere near as in your face or present than it is by the ocean or on Cape Cod. The city environment kind of subdues that.

So what I was thinking is if an urban environment can subdue weather that way – push it to our peripheral vision – then how can anyone living in a city really understand climate change and the whole complexity of climate change.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the communities where climate change is very evident are rural communities. You go to Cape Cod and the people that live there say, “Of course, it’s changing. We see it We see it every day.” I think that reality is clouded much more in an urban environment.

It would seem that would have profound policy impacts, because, projections are that going forward, a larger and larger percentage of the world’s population will live in cities…

Oh, I agree. I mean, I think it’s kind of curious just to look at the weather report on television – it’s almost always about the car. It’s how is the weather going to effect your commute. So people experience weather mainly through the car. I find that so interesting.

What about renewable energy; how has your art influenced how you see renewables and concepts like sustainability?

Well, I’d answer that this way – weather observing is, at its heart, observing energy. So living on Cape Cod, as I did, and being surrounded by all this energy – when you go and view all this energy every day, it’s just amazing that we are not doing more to harness it. It seems very evident to me that that’s where the future lies. And it’s just frustrating when you go from that to living in a city clogged up with cars.

Do you have a sense of where your work is taking you?

I don’t know where it is going, but I wouldn’t be doing it if I knew where this was going [laughs]. I generally let the information and how I understand the information guide me. That’s how the shifts in my art have occurred. I follow that gut feeling.

I think the longer you study a given subject, the more you realize that it is less back and white than you thought, and you begin to become more intrigued by these nuances and echoes that you didn’t really hear before but now you do. I think the more you learn about a subject matter, the more you realize you don’t know about the subject and that’s the wonderful thing about focusing on… anything… for a long period of time. You really begin to hear its nuances and see them more and more; The more those reveal themselves the more translation processes will reveal themselves as well.

For additional information: