Inspired by what they see as the American buying public’s widespread concern about climate change and US dependence on imported oil, US and international car makers are moving to satisfy what they hope is pent-up and brewing demand, with several new models – at a variety of price points – expected to be on the market by year’s end.

And yet, while they might find a place in some parking spaces and driveways across the US, it’s difficult to imagine the Chevy Volt, Ford Fusion, Nissan Leaf or Toyota Prius supplanting gas-powered cars in a place that’s just important to their ultimate success -- the American psyche.

Would Steve McQueen trade in the 1968 Ford Mustang GT 390 Fastback with which he careened through the streets of San Francisco in Bullitt for BMW’s new, all-electric ActiveE, a car that's top speed is electronically limited to about 90 miles per hour?

Would the spontaneity of the care-free Salvatore “Sal” Paradise and Dean Moriarty be anywhere near as compelling in Jack Kerouac’s On The Road, if they had to stop 50 or even 100 miles down the highway and wait for four hours while their plug-in charged?

From the outset, Americans loved the internal combustion engine and the freedom it wrought. Generations of American men got their fingers and t-shirts blackened with grease as they made repairs and performed needed maintenances on their car of the moment.

And while it can very persuasively be argued that this auto-mania has had its downside – adversely impacting the aforementioned climate and leading to a misallocation of now crumbling infrastructure – the internal combustion engine is proving stubbornly resistant to replacement.

Despite a KPMG survey of 200 auto industry executives last year that found a strong belief electric vehicles will account for as much as 10 percent of world car sales by 2025, two recent studies by Exxon Mobil and BP suggest electric cars and hybrids will make up just four percent to five percent of all cars in the world by mid-century.

Clearly, if the new era of the electric and the hybrid is going to take hold and the vehicles make real inroads, it seems certain that along with improvements in technology and design, the manufacturers and other proponents of these cars need to also find a way to restrike that old chord.

How?

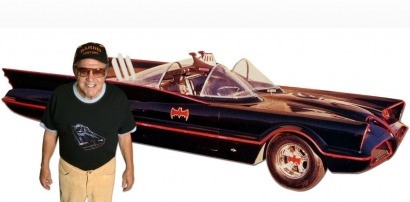

For an answer we turned to George Barris, the reknowned “King of the Kustomizers,” who helped usher in the custom car and hot rod era of the 1940s, 50’s and 60’s, and went on to even wider fame as the creator of the Batmobile, the Munsters Koach, the later Kitt from Knight Rider and a slew of other eye-popping cars for American television and movies.

Electrifying projects in the works

Amazingly, at 86, Barris still works every day at his auto design studio, Barris Kustom Industries, in North Hollywood, California, and when he’s in the grip of inspiration, the sturdy senior of Greek extraction has been known to work as late as nine or 10 o’clock at night.

Nearly as surprising is that Barris, a man whose many classic designs are almost Valentines to the power and promise of the internal combustion engine, is quite enamored with electric and hybrid vehicles, and has been for years.

“I’m excited about anything that’s an expansion on the idea of doing something bigger and better and different,” Barris says. “I think it’s great to have electric cars.”

But as he reveals later, he also thinks the designers and manufacturers of these vehicles have a lot of work to do before there’s one in every driveway.

Barris’s connection to vehicles powered by renewable sources extends all the way back to the 1970s, and was revived in 2005, when Toyota and The New York Times challenged him to apply his customizing wizardry to the Prius – giving him a 10-day time limit and meager $9,000 budget.

“They asked what I thought of the Prius and I said I thought it was a good idea,” Barris recalls. “It was an electric car. It was a hybrid. You’re on battery and then you’re on gas. I said it was a great idea.”

The body, however, left much to be desired in the eyes of the life-long customizer who the author/journalist Tom Wolfe likened to Picasso in a famous article – “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby” – published nearly 50 years ago in Esquire magazine.

“I had just done some work on a movie, “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles”, and I guess that had an impact, because the next thing I said was, “Your car is great, but it looks like a turtle.”

“They said, ‘Oh, well Mr. Barris, what would you do?’ And I said, there’s a lot of things you can do,” Barris says.

That led to the 10 day, $9,000 assignment, but the constraints – which also included his not tampering with the car’s electronics or mechanics -- were a little daunting.

“Both [constraints] are wrong. You can’t do much in that time or on that budget, but I loved the challenge,” he says.

The finished product appeared in The New York Times in September 2005. The article described the formerly drab Prius they left with Barris as looking “lithe but powerful” and “dressed outlandishly.”

Barris made the nose longer and taller, “So that it doesn’t cheat the wind so much as cleave it.” He also added flared fenders, 18-inch wheels and an aerodynamic rear spoiler.

Then, as a finishing touch, he painted the car Tangerine Gold-Astra Green.

“You could have no engine under there, and it will still catch people’s attention,” Barris quipped at the time.

Today, he’s got a solar-augmented Ford Fusion in the works for Galpin Ford, a dealership in the Los Angeles suburb of North Hills, Calif., and what he describes as “the world’s first four-door, electric ‘Bat Car’”, his latest take off on perhaps his most famous design, the Batmobile.

“I don’t call it a ‘Batmobile’ per se, because each time I do one it truly is a markedly different car, but there are similarities,” Barris says. “I’m still designing it at the moment, but I am hoping to build it on a Ford Fusion chassis.”

And why exactly, is he still doing this?

“Because of the enjoyment I get out of it,” Barris says. “I do something I love and it’s something that makes people happy. That satisfies me tremendously.”

A single-minded love of cars

Barris was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1925, but after his mother died just three years later, he and his older brother Sam were sent to Roseville, California, a small community outside the state capital of Sacramento, to live with an aunt and uncle who raised the boys as their own sons.

The couple ran a small hotel and restaurant, and as the brothers grew up, they often helped out in the restaurant while biding their free time building balsa wood models of cars.

“We’d take these models down to the Woolworth’s Five-and-Dime store and enter contests, but the contests at the time were really geared toward airplane models,” Barris said as his daughter Joji attended to business in an adjacent office.

“Nobody was doing model cars at the time, and so what we were doing was seen as quite different,” he says.

And as it turned out, it was a sure sign of things to come.

Although Barris’ adoptive parents hoped the boys would ultimately go into the restaurant business, both caught the car bug bad and wasted no time in making that clear.

“Basically, it boiled down to a conversation where I said, ‘I like cars,’ ‘We both like cars,’ and I said I wanted to customize cars – probably even more than my brother did,” he explains.

To his never-ending gratitude, his parents did not quash the boys’ desire, but instead gifted them with a 1925 Buick to practice on.

“It wasn’t running, but at least it was something I could play with and get running,” Barris says.

Right from the start, however, appearances mattered. As soon as he got the old car running, he made his way back to the five-and-dime store and bought some house paint that he applied to the fenders with a brush. Pots and pans were soon serving double duty as hub caps.

“Then I went into my aunt’s bedroom and took the little gold knobs off her cabinets and installed them on the grill,” he says.

Beaming, he adds, “Lo and behold, everybody loved it. It was the greatest looking 1925 Buick you ever saw in your life!”

Barris’ aunt, as you might imagine, felt otherwise; soon, the budding customizer found himself grounded – and not for the last time due to his obsession.

With that, Barris reels off a series of recollections of his childhood a series of stories that sound like something out of the Our Gang comedies of his childhood.

A bright student, Barris nevertheless fell afoul of his teachers because of his single-minded dedication to cars.

“I didn’t want to do anything that everybody else wanted to do,” he says. “Regretfully, I didn’t have a good reputation in school … I got kicked out of everyone I attended.”

Barris credits his teachers for trying, but their attempts to meet his passion halfway were always off the mark.

Because of his love of cars, one school put him in metal shop.

“The problem was, I wanted to learn how to shape metal, and here I was, making drain pipe … so I said, ‘No. I quit,’” he recalls.

During the ensuing conversation, Barris proclaimed he wanted to design cars, so they next tried to satisfy him with an art class.

“But they had me drawing flowers,” he says, sounding nearly as pained as he must have sounded 70 years ago.

At an impasse, Barris says the school kicked him out. He fared better at his second school, thanks, he says, to his being a star in track and in basketball.

At the same time, he was becoming steeped in the “black art” of body work, hanging around local auto shops like Jones Brothers in Roseville and Brown’s and Bertolucci’s in Sacramento.

“They’d throw me a piece of metal and show me how to light the seven-inch torch and they’d say, ‘Okay, go for it, kid.’ So I’d start working the metal, hammering it with a dolly and a hammer, and that’s how I learned to shape metal,” Barris says.

Another customizer patiently showed him had to roll metal by hand to make “fade away” fenders.

But when it came time for him to graduate, the principal balked at handing him a diploma.

“He was praising one student after another – you’ll be a great doctor; and you’ll be a fine lawyer – but when he got to me he said, “’And you, you’re the least likely to succeed.’”

Drag racer and businessman

By this time, Sam Barris was in the service, and George headed south for Los Angeles to start his customizing career.

Inevitably, he made the journey behind the wheel of one of his creations. And just as inevitably, the journey inspired another story.

“I was driving down Vermont Avenue in a ’36 Ford, looked at some little girl walking down the street, and wound up rear-ending the guy in front of me,” Barris said.

The accident precipitated a trip into the nearest body shop, where Barris asked if he could fix his car. The manager said, ‘Sure,’ and pretty soon patrons and employees were watching his handy work.

“They started asking, ‘Will you do this for me?’ ‘Can you do that on my car?’ And I said, well, I guess I am in the right place to start me own shop.”

The year was 1944, and a year later, newly discharged from the service, Sam Barris arrived in Los Angeles and was soon in business with his brother. They called the business the “Barris Brother’s Custom Shop,” and from there, things really began to take off.

Meanwhile, George found another way to tweak authority.

“I was an illegal drag racer,” he says in a manner to suggest it really was an unavoidable turn of events.

“I did my first drag race in a little town near here called Culver City, and we would drag race up and down and the cops would chase us all the time, but they never could catch is,” Barris said.

“One morning, I went out to my car and found bullet holes in the trunk,” he says, his voice growing warm at the memory. “They were so mad they were shooting at us – but they still couldn’t catch us.”

Ground zero for these races was the Piccadilly Drive-In, where car enthusiasts would gather to show off their latest handiwork. Inevitably, a challenge would be thrown down, and soon the racers would be heading over to Sepulveda Boulevard where the two racers would line up on either side of the center line.

Friends of the participants would block off each end of the road, and if an inconvenienced driver happened on the scene and squawked, they’d be told in no uncertain terms that they could proceed, but only at their own, unquestionable risk.

“It was really dramatic, no question. But it was also good clean fun,” Barris says. “By this time I had started a club called Kustoms of Los Angeles, and I had just a couple of simple rules: You don’t smoke, you don’t drink … and I hate drugs. But I said to the guys, I’m going to allow you two bad habits – cars and girls,” Barris said.

He adds impishly, “That made it easy for people to follow.”

At the time, Hot Rodding was becoming a phenomenon in Southern California. A fellow car nut, Robert E. Petersen, founded Hot Rod magazine, and then established a magazine publishing empire that would include Motor Trend, Car Craft and a score of other hobbyist titles.

For the record, hot rods are considered distinct from custom cars, with the former being street cars bulked up for speed, usually by the owners themselves and mainly for racing, while the former are enjoyed more for their visual impact with the work being done mostly by professionals, like Barris, in specialized body shops.

The two communities could be a combustible mixture, as is illustrated by Barris’ lengthy remembrances of colorful street fights, some of which ended with a night, or at least a few hours, in jail.

But the excitement of the drag races – not to mention the eye-popping visuals of the customs – soon jointly caught the attention of nearby Hollywood, which by the 1950s was churning out features by the boatload to capitalize on the newly affluent teenage market.

Hollywood beckons

Barris says the first time his handiwork appeared in a film was in 1958, when MGM approached him to work on High School Confidential, a teenage crime drama featuring Russ Tamblyn, Mamie Van Doren, John Drew Barrymore and rocker Jerry Lee Lewis.

Despite a tagline on the old movie poster that described the movie as depicting “a teacher’s nightmare” and “a teenage jungle,” Barris proudly says, “the whole thing was about the life we were leading.”

“This interested more people in doing things like that, which meant for us, more movie work followed … and then along came the 1960s and we started showing up on the small screen too,” he says.

In fact, what transpired was a succession of popular television shows – almost all still shown daily somewhere today – that featured Barris-customized vehicles, often, as in the case of the Batmobile, as critical elements in the story lines.

“First came The Beverly Hillbillies, then the Munsters, then Batman, then the Monkees, then The Green Hornet … and it continued on up through Knight Rider and the Dukes of Hazzard and its never really stopped,” Barris says.

“It just kept getting stronger and bigger, and now we’re known all over the world for the custom cars that I created,” he adds.

At some time between his early exploits as a car customizer and his high-profile work in American television, Barris became known for his dedication for form and his ability to change just about any automobile out of Detroit into a streamlined, one-of-a-kind creation befitting the then-just dawning space age.

He particularly loved working on the 1951 Mercury, a model that he’s customized in entirely different ways hundreds, if not thousands of times over the last four decades. And therein lies a clue not only to his creative philosophy, but also what he believes is imperative to imbuing a car with the ability to stir the imagination.

“To be different is important,” he says, his tone growing serious. “It’s important not to be another ‘Me-too.’ Don’t do something the same as everybody else.

“Everybody chops a Mercury the way I do it,” Barris continues, referring to the practice of lowering the top or roof of the car by cutting and removing material from the window posts and re-welding, giving the vehicle a sleeker appearance.

“But what I think they miss is that every Mercury I’ve done is actually different from the last. But they just pick one version or other that I’ve done – usually the first one, the Hirohata Mercury, which was named for its owner, Bob Hirohata -- and follow it like a template,” he adds with a hint of disappointment.

“It’s funny, but I think that whatever you do, if you’re going to be successful at it, you have to have a certain feeling for it … I don’t care if you’re a hairdresser, an artists, a movie star … whatever it is … it has to be a natural extension of who you are,” Barris says. “For example, I can be driving down the street and see a set of tail lights on a car in front of me and something will go off in my head; I’ll say, ‘Wait a minute, those Chrysler tail lights … if I take those and turn them upside down and put them on a slant on the back fender of 51 Mercury, that would look groovy.

“That’s how I worked back in the day and that’s what I still do today,” he adds.

Pressed about what he’s learned about creativity over the years, Barris sighs.

“To gain creativity is to look at what somebody else has done and improve it,” he says. “Again, don’t make it look like another ‘Me-too’; do something to enhance what you’re given.”

By way of example, Barris points to his early – and arguably most memorable -- television work.

Whenever he got a call, he and his wife Shirley, who became his business partner at about the same time that his brother decided to retire from it, would meet with the show’s producers and director to hear what they had in mind.

Being television people and not necessarily car buffs, their ideas where often pretty straight-forward, Barris said.

The team behind The Beverly Hillbillies, for instance, merely wanted the family, who accidently struck it rich by discovering oil near their mountain home and moved to Beverly Hills, to drive an old jalopy.

Okay, fine, for a start, Barris thought. But as he drove down California’s Highway 10 one day, driving toward San Bernadino, he noticed a 1922 Oldsmobile sitting in front of a feed store.

It had four doors and its back had already been cut off so that the owner could haul hay for it.

“I jumped out and photographed right away, and went directly back to the studio,” he remembers. “I said, ‘What do you think of this?’ And they said, ‘George, that’s perfect.’

But perfection just wouldn’t do. Before the show went on the air, Barris added a new and distinctive touch to the back: A rocking chair for the “granny” to ride in.

The evolution of the Munsters Koach followed a similar line; the show’s producers originally envisioned the family consisting of Herman and Lilly Munster, mad scientist/vampire Grandpa, son and werewolf Eddie Munster and ‘normal’ daughter Marilyn, riding around in an old hearse.

“I said, ‘Wow, with this family you’ve got, we have to make something nice,’” Barris says.

The customizer went back to his shop and, as he still does to this day, took out a bunch of photographs of cars, and then cut and paste them into a semblance of the idea he was after.

“With the Munsters Koach, I started with photos of a Model T Ford and put them together to create a three-door model, and then put a little seat in the back for Eddie to ride in,” he explains.

But he didn’t dispense of the funeral notions of the producers, affixing casket handles and other touches to the car’s body.

Sometimes necessity was the mother of invention.

The Batmobile, arguably Barris Kustom’s most famous creation, is actually based on a Lincoln Futura, a concept car of the mid-1950s that had been built by Ghia of Italy and sat, unused in Barris’ collection of automobiles.

Busy with multiple television shows and the demands of his business, which was now turning out custom cars for celebrities like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Elvis Presley, Barris was unexpectedly asked by ABC television to create a car for a super hero show that was going into production in just three weeks’ time.

With no time to pull out his photos and scissors and paste to conjure an entirely new vision, Barris decided the Futura would be the perfect base on which to build up a Batmobile.

The classic creation includes a front end modeled on a bat’s face, a double bubble windshield made of streamlined aircraft windows, and scores of gadgets including a “Batscope”, a T-arm accelerator and even a “Bateye” switch for anti-theft control.

Solar-powered Supervan

The Batmobile also “utilized” computer technology – at least fictionally – to communicate with its base, the Batcave located beneath “stately” Wayne Manor, and lasers to augment other crime-fighting tools.

However, it wasn’t until 1977 and an otherwise forgettable feature called “Supervan,” that Barris employed renewable energy in one of his customized design.

The plot, summed up in one line on the IMDb website, revolves around a man named Clint who entered a solar-powered van called Vandora into a competition called Freakout. Also notably, Barris himself appears in the movie as, what else, the King of Kustomizers.

Barris’ website describes the transformed Dodge Sportsman Van that in an earlier, late 1960s custom iteration had been called “the Love Machine,” as “the ultimate in futuristic motoring with solar energy.”

According to Barris, the Supervan started out as a battery-powered electric, but because it was filled with a radio, television and numerous turntables, the vehicle’s charge just didn’t last all that long.

“Before you knew it, the battery would be dead and you couldn’t drive it,” Barris says.

At the time, California was in the midst of its first solar power boom, and Barris quickly installed solar panels on the roof to run all of the van’s accessories.

The experience left him with a deep appreciation for the potential of electric vehicles, particularly the potential of powering them, at least in part, from solar energy.

At the same time, he admits to being a little disappointed with the hybrids and electric models that had been produced so far.

“I’ve looked at what they are doing with electric cars, and frankly, I think they’ve still got a way to go," Barris says. “You’ve got cars out there that get little more than 48 miles to a charge, and well, c’mon – 48 miles worth of power isn’t even going to get you down the street in Los Angeles.”

With solar power, he says, one never needs to worry about running out of juice or desperately searching for a charging station because even when stopped or parked the PV panels on the car will keep soaking in the sun’s rays and recharge the battery in the process.

“Some people are blessed to be artists, some people are blessed to be clothing designers or movie directors or whatever, and luckily, I was blessed to be able to look at cars and come up with ideas of what they could do and how to market them.”

Ah, the marketing.

Although Barris will always be known for his career as a customizer, he’s also seen as a master of marketing. Where most might have been content to have their creations seen every week on hit television shows and on movie screen, Barris seemed intent during this period to have his name plastered everywhere he could.

In the late 1950’s, Revell began making plastic model kits of his cars, and soon another toy company, AMT, was marketing a line of Barris-based plastic models of its own. Today the customizer’s website includes DVDs, books, postcards, toys and model kits, and even a line of bicycles.

Today, he remains a much in demand presence at car shows and continues to host an annual Custom Car gathering each May at his old stomping ground, the Piccadilly Drive-In. Last year the event drew 2,000 cars and more than 40,000 spectators on the Saturday before Mother’s Day.

So what will it take for the electric car or hybrid to capture the public’s imagination the way traditional cars did?

“You have to work out some way to make an expansion of the usage of the car and the looks of the car,” Barris says. “So that means, don’t make it ugly, number one, and number two, you’ve got to get some good value with it, financially, and also in terms of its design and its usage.

“So there are a lot of points to hit, but, you know, it can be done,” he says. “I mean, look at my career. I’m just one guy. I’m not a big company. I don’t have a Ford Motor Company or other major player backing me, but I think there’s a task at hand to accomplish and I’m inspired to do it. My whole life, whenever something new comes out, I ask myself what I can do to make it better.”

Years ago, Barris says, he became intrigued with the potential for utilizing solar panels and solar energy is automotive design.

Today, he’s still thinking of new ways to apply that notion.

“I’ve been following the progress of companies overseas that are doing things with solar and cars, and there are some interesting ideas out there, but what I keep coming back to is that when you incorporate solar into your home, you do it with sheets,” he says.

“So awhile back, I had something made out of solar cells that I could incorporate into a sun roof and that would kind of work the same way,” Barris continues. “You push a button and the roof rolls back to reveal a solar-energizing sheet. Another idea I have is putting solar panels on the spoiler of the car and being able to push a button to change their direction and point them toward the sun.

“Now, of course, I’m only going by my imagination. I don’t have any formal education in solar systems. I’m self-taught and learned much of what I know from what I did way back on the Supervan,” he says. “But the way I see it, incorporating solar in this way would keep the batteries charged, and because you’d have some ability to change the direction of the panels, you’d be able to charge the battery and run the car very efficiently.”

From the pure design perspective, Barris says he thinks the makers of electric and hybrid cars are getting better with time – evidence, he says, of their “finding out people will buy a product that was made with an emphasis on design.

“Of course, the Prius sold pretty well when it first came on the market, but it had the benefit of being the first one and also of its debut coinciding with escalating gas prices in the US,” Barris says. “The market was full of people who were saying to themselves, ‘Hey man, I’ve got to find another way.’

“You can’t rely on that now. Those dynamics are gone,” he continued. “So now you really have to address the issue of mileage per charge and the availability of charging stations. But then, there’s a whole other level of considerations. For instance, suppose you find a charging station, what are you going to be asked to pay for that charge? And how long with the charge take and what will you do while you’re waiting?”

The other thing Barris believes electric and hybrid manufacturers need to address is the economics of electric charging compared to filing up at the pump.

Early on, he says, many people grew discouraged by the fact that they didn’t seem to be saving money charging their electric car when compared to filing up at the pump. Although they liked and embraced the opportunity to charge their cars at home, they soon saw their electric bills rising dramatically.

“So, are you going to save money? Think about it,” Barris says. Am I saving money because I’m using all my electricity, which I still have to pay for, compared to the amount of money I used to pay for gas? That’s a question the consumer really needs to be able to answer in the affirmative, and so it’s something these manufacturers have to figure out.”

“Hybrids like the Prius are a different dynamic, because they do have a gas engine and will charge the battery while running on gas, but car like the Chevy Volt, you know, you have to pull over and charge it,” he says.

With all this said, Barris admits he does go back and forth on electric vehicles sometimes.

“It’s a case of, ‘Yes, I do like it and no, I don’t,’” he says with a laugh. “I guess the thing that somehow needs to be communicated is: what’s the inspiration? What are they doing to improve it? And, what are they giving us that’s saving us money?

“Now, there’s no question that people working on these cars are coming up with many good ideas, but remember, cars are a much bigger investment than they used to be – a car, a good car, used to cost $1,500; now you’re talking more like $150,000,” he says.

Reflecting on the custom car and hot rod culture that he as much as anybody helped bring to the fore in American life, Barris isn’t shy in explaining why it took hold that way that it did.

“I was because we created something that was inspiring,” he says. “We created something that was enjoyable and that gave people something that meant more than simply being a mode of transportation or, in the case of customs, a hobby.

“The custom car movement is all about doing different things, getting involved with people, meeting and greeting them, and exchanging ideas that lead to improvements and innovations,” he says, and the thought leads him back to electric cars and hybrids.

“I think you need to improve the design of the car to the point that that design, on its own, is a benefit of buying it,” he says. “By all means, make it a cost effective purchase, improve the mechanical conditions … but always keep in mind that a lot of what people envision when they buy a car is the enjoyment they are going to have driving it.

“And also, don’t shirk on styling. Styling is number one,” Barris says. “You’ve got to make it look enjoyable to drive, and you’ve got to make it look different – don’t make it look like another ‘Me-too regular.’”

For additional information: