The original project used submerged turbines anchored to the sea floor through mooring cables that converted the kinetic energy of sustained natural currents into usable electricity, which was then delivered by cables to the land. The initial phase of the project was successful, but the OIST researchers also wanted an ocean energy source that was cheap and easy to maintain.

This is where the energy of the ocean’s waves at the shoreline came into play. “Particularly in Japan, if you go around the beach you’ll find many tetrapods,” Professor Shintake explains. Tetrapods are concrete structures shaped somewhat like pyramids that are often placed along a coastline to weaken the force of incoming waves and protect the shore from erosion. “Surprisingly, 30% of the seashore in mainland Japan is covered with tetrapods and wave breakers.” Replacing these with “intelligent” tetrapods and wave breakers, Shintake explains, with turbines attached to or near them, would both generate energy as well as help protect the coasts.

“Using just 1% of the seashore of mainland Japan can [generate] about 10 GW [of energy], which is equivalent to 10 nuclear power plants,” Professor Shintake explains. “That’s huge.”

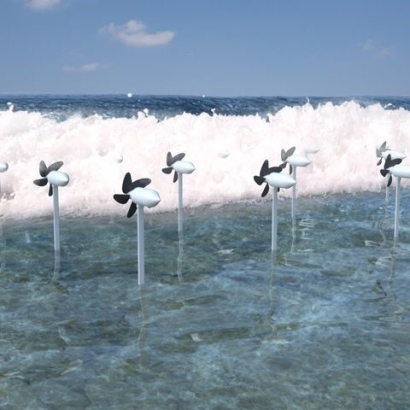

Building on this idea, the OIST researchers launched The Wave Energy Converter (WEC) project. The project involves using multiple turbines located near the tetrapods or among coral reefs. Each location would allow the turbines to generate clean and renewable energy and to help protect the coasts from erosion while being affordable for those with limited funding and infrastructure.

The blade design and materials used in the turbines are inspired by dolphin fins—they are flexible, and thus able to release stress rather than remain rigid and risk breakage. The supporting structure is also flexible, “like a flower,” Professor Shintake explains. “The stem of a flower bends back against the wind,” and so, too, do the turbines bend along their anchoring axes. They are also built to be safe for surrounding marine life—the blades rotate at a carefully calculated speed that allows creatures caught among them to escape.

Existing maintenance routes for the tetrapods could be used for the turbines, which the team predicts would have a lifespan of approximately 10 years.

Professor Shintake and the Unit researchers are preparing to install the turbines—half-scale models, with 0.35-meter diameter turbines—for their first commercial experiment. The project includes installing two WEC turbines that will power LEDs for a demonstration.

“I’m imagining the planet two hundred years later,” Professor Shintake says. “I hope these [turbines] will be working hard quietly, and nicely, on each beach on which they have been installed.”

For information: Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

Photo courtesy of OIST