Solar or photovoltaic cells represent one of the best possible technologies for providing an absolutely clean and virtually inexhaustible source of energy to power our civilization. However, for this dream to be realised, solar cells need to be made from inexpensive elements using low-cost, less energy-intensive processing chemistry, and they need to efficiently and cost-competitively convert sunlight into electricity.

A team of researchers with the US Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has now demonstrated two out of three of these requirements with a promising start on the third.

Peidong Yang, a chemist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division, led the development of a solution-based technique for fabricating core/shell nanowire solar cells using the semiconductors cadmium sulphide for the core and copper sulphide for the shell. These inexpensive and easy-to-make nanowire solar cells boasted open-circuit voltage and fill factor values superior to conventional planar solar cells. Together, the open-circuit voltage and fill factor determine the maximum energy that a solar cell can produce. In addition, the new nanowires also demonstrated an energy conversion efficiency of 5.4 percent, which is comparable to planar solar cells.

“This is the first time a solution based cation-exchange chemistry technique has been used for the production of high quality single-crystalline cadmium sulphide/copper sulphide core/shell nanowires,” Yang says. “Our achievement, together with the increased light absorption we have previously demonstrated in nanowire arrays through light trapping, indicates that core/shell nanowires are truly promising for future solar cell technology.”

Typical solar cells today are made from ultra-pure single crystal silicon wafers that require about 100 micrometres in thickness of this very expensive material to absorb enough solar light. Furthermore, the high-level of crystal purification required makes the fabrication of even the simplest silicon-based planar solar cell a complex, energy-intensive and costly process.

Thinner than a human hair

A highly promising alternative would be semiconductor nanowires – one-dimensional strips of materials whose width measures only one-thousandth that of a human hair but whose length may stretch up to the millimetre scale. Solar cells made from nanowires offer a number of advantages over conventional planar solar cells, including better charge separation and collection capabilities, plus they can be made from Earth abundant materials rather than highly processed silicon. To date, however, the lower efficiencies of nanowire-based solar cells have outweighed their benefits.

“Nanowire solar cells in the past have demonstrated fill factors and open-circuit voltages far inferior to those of their planar counterparts,” Yang says. “Possible reasons for this poor performance include surface recombination and poor control over the quality of the p–n junctions when high-temperature doping processes are used.”

At the heart of all solar cells are two separate layers of material, one with an abundance of electrons that function as a negative pole, and one with an abundance of electron holes (positively-charged energy spaces) that function as a positive pole. When photons from the sun are absorbed, their energy is used to create electron-hole pairs, which are then separated at the p-n junction – the interface between the two layers – and collected as electricity.

Nanowires become solar cells

About a year ago, working with silicon, Yang and members of his research group developed a relatively inexpensive way to replace the planar p-n junctions of conventional solar cells with a radial p-n junction, in which a layer of n-type silicon formed a shell around a p-type silicon nanowire core. This geometry effectively turned each individual nanowire into a photovoltaic cell and greatly improved the light-trapping capabilities of silicon-based photovoltaic thin films.

Now they have applied this strategy to the fabrication of core/shell nanowires using cadmium sulphide and copper sulphide, but this time using solution chemistry. These core/shell nanowires were prepared using a solution-based cation (negative ion) exchange reaction that was originally developed by chemist Paul Alivisatos and his research group to make quantum dots and nanorods. Alivisatos is now the director of Berkeley Lab, and UC Berkeley’s Larry and Diane Bock Professor of Nanotechnology.

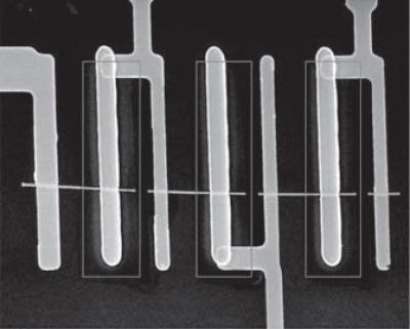

“The initial cadmium sulphide nanowires were synthesized by physical vapor transport using a vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) mechanism rather than wet chemistry, which gave us better quality material and greater physical length, but certainly they can also be made using solution process” Yang says. “The as-grown single-crystalline cadmium sulphide nanowires have diameters of between 100 and 400 nanometres and lengths up to 50 millimetres.”

The cadmium sulphide nanowires were then dipped into a solution of copper chloride at a temperature of 50 degrees Celsius and kept there for 5 to 10 seconds. The cation exchange reaction converted the surface layer of the cadmium sulphide into a copper sulphide shell.

“The solution-based cation exchange reaction provides us with an easy, low-cost method to prepare high-quality hetero-epitaxial nanomaterials,” Yang says. “Furthermore, it circumvents the difficulties of high-temperature doping and deposition for typical vapour phase production methods, which suggests much lower fabrication costs and better reproducibility. All we really need are beakers and flasks for this solution-based process. There’s none of the high fabrication costs associated with gas-phase epitaxial chemical vapour deposition and molecular beam epitaxy, the techniques most used today to fabricate semiconductor nanowires.”

Yang and his colleagues believe they can improve the energy conversion efficiency of their solar cell nanowires by increasing the amount of copper sulphide shell material. For their technology to be commercially viable, they need to reach an energy conversion efficiency of at least ten percent.

For additional information: