“In those situations, you typically can’t accept total loss of power,” said Brent Houchens, a mechanical engineer at Sandia National Laboratories.

That is one reason why Houchens, along with collaborators at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Idaho National Laboratory, spent the last four years exploring how wind energy could power both military and disaster relief efforts—both of which need fast and reliable power to succeed. Funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Wind Energy Technologies Office, the Defense and Disaster Deployable Turbine project brought technology developers and researchers together with military and disaster response organizations to learn what kind of wind turbine system could best serve their needs.

“It needs to be portable, assemble quickly, and get to work,” said Brent Summerville, a distributed wind energy systems engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and a collaborator on the project. “That’s a whole different challenge than the wind energy industry was used to.”

In war and disaster zones, quick and reliable power can save lives. And while diesel-powered generators are convenient and easy to operate—often with just a quick push of a button—those generators require a steady stream of liquid fuel. Depending on how long the operation lasts (some disaster-struck communities need years to rebuild) and how remote the location, those constant shipments can come with steep emissions on top of the extra costs and risks.

To offset at least some of their reliance on liquid fuels, defense and disaster response industries started to look to renewable energy as a potential solution. Sun and wind do not need to be trucked in; and while modular solar panels are easy to ship and install, not all locations have a steady stream of sunshine. Adding wind energy (plus energy storage, like batteries) could help maintain power for communications, water filtration, heat, lights, and medical equipment.

And yet, designing a deployable wind turbine—one that is quick and easy to ship and install—is not a simple task. To erect a traditional land-based wind turbine, specialists pour concrete and use cranes to place its tall tower. But, Summerville said, “It’s a whole different strategy when you want the turbine to arrive and deploy quickly. That’s very complex.”

“You have to strike a balance,” Summerville continued. If the turbine is divided into 50 small parts, like an Ikea bookcase, it is easy to ship but hard to assemble. A fully formed turbine would be hard to ship but easy to erect. “It doesn't necessarily need to be the cheapest cost of energy,” Summerville said. “But it does need to be easily deployed, transportable, easy to operate, and reliable.”

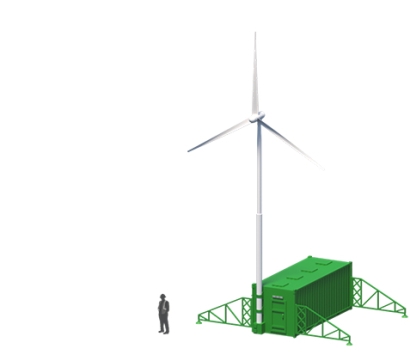

Over the last four years, the multilaboratory team analyzed whether it is possible to build wind turbine “transformers” that could fit those needs. Both the military and the American Red Cross prefer to use 20-foot shipping containers. So, Summerville and his team figured out how much wind turbine could fit in these standard containers (and even whether the container itself could be used as a base for the turbine once it arrives on location).

Turns out, a roughly 20-kilowatt wind turbine, plus a few solar panels and batteries, could all fit nicely in those 20-foot boxes. That same container could fit even more kilowatts of wind energy from the less-well-proven technology of airborne wind turbines, which are like high-flying kites tethered to the ground. “Military and disaster relief organizations want something that’s going to work,” Summerville said. “Eventually, if it’s proven to be reliable, airborne wind could be a good fit.”

As a final step in the project, the project team hosted a virtual workshop in June 2022 (with a follow-up report soon to be posted on Sandia National Laboratories’ project website) for wind turbine suppliers to meet their potential customers: military and disaster response organizations. Both customers reported similar needs, including simple, robust technologies that are easy to use, operate, and integrate with other energy sources. Technology developers voiced one major concern: financing. Representatives from both groups indicated that they want a test bed—a way to try out various technologies to verify they are ready to go to war and help save lives.

Some lower-risk trials are already planned, Houchens said. Researchers based at climate monitoring sites in the Arctic can pay as much as $100 per equivalent gallon of diesel, for example, and plans to give the new deployable wind technologies a try. And a few remote communities in Alaska will pair solar power, wind energy, and diesel to reduce their overall dependence on fossil fuels.

This way, Houchens said, the technologies will not have to prove themselves “in scenarios where people’s lives are on the line.”

Read about the Defense and Disaster Deployable Turbine project and stay tuned for a forthcoming summary report on the June 2022 stakeholder workshop. Learn more about NREL's research and development in distributed wind energy via NREL's wind energy newsletter.

Illustration courtesy of NREL